How two TV Academy experiments in the ’60s and ’70s went ‘super’ wrong

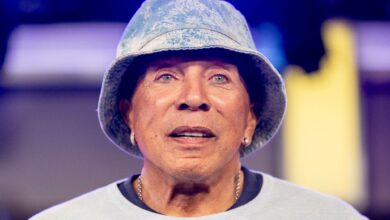

At 98, Dick Van Dyke is almost a quarter century older than the Emmys (who are 76 years old this year). Which makes it all the more amazing that he’s still a force when it comes to TV’s biggest prize. Not only did he score a Daytime Emmy this year, breaking records as the oldest winner ever, but he was also the subject of the current Emmy-nominated CBS special “Dick Van Dyke 98 Years of Magic.”

Van Dyke, who last won a Primetime Emmy in 1977 (for “Van Dyke and Company”), is not eligible for any of the four nominations “98 Years of Magic” received – including outstanding pre-recorded variety special

– although his star power certainly didn’t hurt. Van Dyke has won a total of four Emmys, but one of them has an interesting asterisk.

As an armchair quarterback, I know I’m always pontificating about ways the Television Academy could improve the Emmy categories or broadcasts. But sometimes radical change isn’t such a good idea.

I’m referring to what happened in 1965, when then-leader Rod Serling put forward the idea of replacing the traditional categories with just four major categories: “program achievements in entertainment,” which honored four shows among fifteen nominees; as well as three ‘individual achievement’ categories with multiple awards for actors and performers, directors and writers.

It was a way to replace the competition with a list of awards, almost like today’s AFI Top 10 lists. That year, instead of winning an Emmy for Outstanding Comedy, “The Dick Van Dyke Show” won that Program Achievement in Entertainment Emmy alongside “Hallmark Hall of Fame: The Magnificent Yankee,” “My Name Is Barbra” and “New York Philharmonic Young People’s’. Concerts.” Van Dyke received an award for actor/performer, as did Leonard Bernstein, Lynn Fontanne, Alfred Lunt and Barbra Streisand.

It was a disaster because the spirit of the competition had completely disappeared. As a result, the TV Academy returned to traditional categories such as comedy and drama the following year. But it hasn’t quite learned its lesson: It’s been 50 years since the organization made another radical attempt to shake up the status quo, with something dubbed the “Super Emmy” in 1974.

This was in many ways even more misleading than the 1965 experiment. In 1974, the TV Academy announced the winners for several Emmys for acting, writing, directing and craft in comedy and drama

categories days before broadcast – robbing them of their moments in front of the camera. It was almost an afterthought after the actual broadcast. Instead, the ceremony focused on pitting the drama and comedy winners against each other for what was nicknamed the “Super Emmy.”

Comedy winner Alan Alda (“MAS*H”) defeated drama winner Telly Savalas (“Kojak”) for actor of the year, and Mary Tyler Moore (“The Mary Tyler Moore Show”) defeated “The Waltons” star Michael Learned for actress of the year. That meant that Alda and Moore won two Emmys in the same year for the same role, while the likes of Savalas and Learned were somehow simultaneous Emmy winners and losers for the exact same roles.

Alda and Moore even criticized the concept on stage while accepting the Super Emmy, and as in 1965, the TV Academy dropped the idea as quickly as it implemented it. Former TV Academy Awards chief John Leverence, who joined the organization a few years after the 1974 mess, reminded me that the Super

The Emmy concept violated a cardinal rule of the awards.

“It was an unfortunate experiment that was not repeated,” he says. “I like to say that number 1: it is a basic principle of the Emmy structure that one Emmy is given for one performance. So if you’re the lead in a drama series, there’s no extra ‘super’ prize attached to it. Second, it is a principle that eligibility is based on genre. You have a leading man for a drama series, you have a leading man for a comedy series, a leading man for a limited series. Third, “protagonist in drama” says that this is the highest you can give. If we add another level, the importance of performance would diminish.”

So why would you do it? At the time, the feeling was that a smaller number of “Super Emmys” would simplify who the year’s major winners were. “However, that theoretical idea was absolutely undermined by the three principles of Emmy eligibility,” Leverence says. “So three fundamental tenets of the Emmy structure – one Emmy for one achievement, appropriateness across genres and levels – were all violated in the 1974 Super Emmy.”

Turns out there’s a science behind it all. Even when it comes to honoring icons like Alan Alda, Mary Tyler Moore and Dick Van Dyke.