How ‘Dark Winds’ David Lynch has channeled to create hallucinations that Joe Laphorn’s generation trauma displays

Spoiler alert: This story contains large spoilers for season 3 of “Dark Winds”, episode 6, entitled “Ábidoo’iidęę (which was told him)” now streaming on AMC.

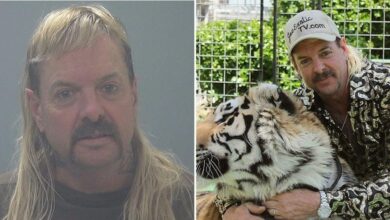

During season 3 of ‘Dark Winds’, Joe Laphorn (Zahn McClarnon) saw monsters, in particular Ye’iitsoh, the Navajo -that is known as Big Giant. He is chased by killing rich villain BJ Vines (John Diehl) in season 2, and the Ye’iitsoh has plagued him.

At the end of last week’s episode he had a meeting with the Ye’iitsoh – but he or was it really? Episode 6 dives in the past of Joe and explains that it has formed its character.

Director Erica Tremblay collaborated with the writers to find out how they can tell this feverish dream scenario that Joe is back in his youth home, with his parents and his younger person. It also focuses on the sensitive issue of his trauma from the past, where he witnesses his cousin, will, abused by a Catholic priest. Tremblay and the writing team understood the weight of responsibility when displaying this specific type of historical trauma. They started looking at it through the lens of being at a boarding school, but that was quickly nixed.

Navajo writer and director Billy Luther grew up with hearing Diné Folklore and History who helped cut the Monster Slayer story. Their idea was that the episode would open with a school game about the Monster Mythology before Joe Laphorn is transported back in time, putting three narrative threads together: the traditional Navajo story of the Hero Twins opposite the Ye’iitsoh; Joe’s current confrontation with a monster that chases him during season 3; And the revelation of a deeply personal youth trauma.

Tremblay discussed the writer’s room process to tackle native historical trauma, to work with McClarnon and why she held his hand during the crucial scene of the episode, and how David Lynch’s visuals helped her with the transition between the worlds.

Take me to the writers room. What was discussed about how you would approach this episode?

This was an episode that lasted a long time to find. At first this was an episode of the boarding school, and for many different reasons I think that the indigenous writers in the room were all of: “If we do a boarding school, there is much that you have to turn out in terms of going back in time.” We had viewed everyone in the ‘Sugarcane’ room, and we had many conversations and decided that it was logical to tackle this through a church in the community, versus to be within the boarding school.

That has opened many ideas about how we could talk about the past of Laphorn, and how the monster is haunting him in this season. But that is an allegory for his trauma, PTSD, guilt and shame.

It was Max Hurwitz (writer and executive producer) who said what if we tell it through a children’s story. Billy Luther is a writer in this episode and is Navajo, and he grew on the story of the Monster Slayer, and then it broke open. Leahorn goes through his subconscious mind while he discovers this traumatic event from childhood that he has pushed it down so deeply that he does not even remember, and through that journey in his subconscious mind he draws all the different reasons from the reasons why he chose the reaction, but also System and ended in his own hands.

The episode opens with the Voice over and the hero Twins that the Ye’iitsoh -mythology performs again in one piece. How did the idea come together?

It was a great way to place the story in Diné’s mythology. This would be different from other episodes of “Dark Winds”, and we are going to take you on a dreamy journey. We have searched high and low to find the space to have this place, and it is a Shriners building, and they have this stage with hand -painted backgrounds from the 1920s, and it has just based the episode based in mythology that feeds the fever dream of Leaporn.

You are dealing with the Monster of Laphorn and his trauma. What discussions did you have with your employees, production designer, composer and cinematographer about how this fever dream needed to look and sound?

It was a real challenge. This episode does a lot, but it has to do a lot within the same budget and the scope as the rest of the episodes. I remember that I was in the PrEP meetings and everyone had ideas. The Dreamscape and Endless Desert in Joe’s Spirit are different colors of the temperature when he is at George, who run around in the real world at night. Those were all targeted decisions.

I have watched a lot of anime, such as ‘Perfect Blue’. David Lynch was a huge inspiration in this episode and think about how you can have creative transitions from one scene to another. I looked at “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “Everything Everywhere All Tegay” when we merged this and looked at Masters of the Craft to bring some of the magic in this episode.

The dinner scene was a great metaphor with the broken sign and being a house in his ‘youth’. What did that mean to represent?

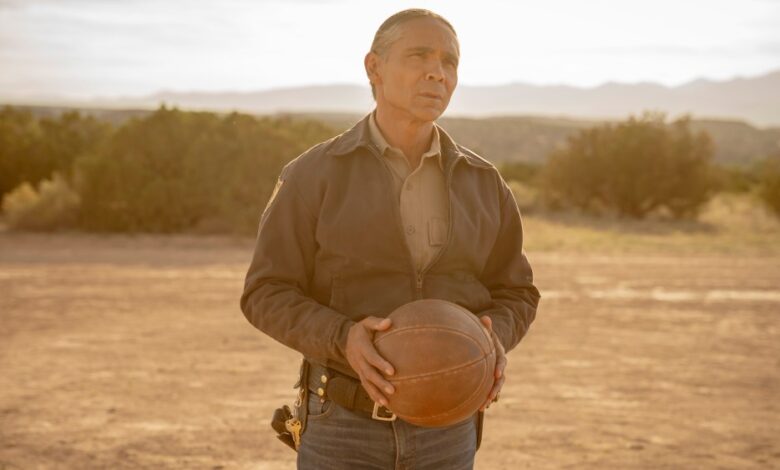

That was one of my favorite transitions in the entire episode. He is in the desert and walks through the door with the basketball. He recognizes it as his youth center, but it is now also his home. And so are dreams – combining things that exist in your life with memories from the past, and they mix together.

He sits down next to whom he knows as George, but while he looks at him, he realizes, “No, that’s me.” He starts combining it that he is in the past. What is interesting is that everyone at that table is Joe Laphorn. Even if he has that conversation with the priest, that is his interpretation of the priest, and in some respects, while the priest asks for forgiveness, he asks for forgiveness. That was one of the first scenes we filmed, because we had to exercise all these different versions of his subconscious mind.

We see Joe Laphorn witnessing Will and the abuse by the priest. How did you want to approach that this part of the historical trauma told?

Very early in the writers’ room, we were talking about these topics and themes, we knew we wanted to go there, and we knew we had to find a way to do it that was accurate for the story of Leaporn, but that also felt like it was not a reconcup with Indians.

It took time and it made sure to dig what that would look like. When we were writing the show, everyone had to feel good about it. We trusted our instincts and non-native writers. We wanted to take the fear we felt and challenge ourselves to find ways to express this dark history in a way that feels authentic, but also not repairers and again training our indigenous viewers and the indigenous people working on the show.

Zahn and I had conversations about how we were going to do this in a way that would leave the least number of figures as indigenous people. We have discussed our experience-we have parents, grandparents and great-grandparents who have been at boarding schools or who have been in situations in which they were abused by the church. We have our experiences in life, in which our way of life is challenged by Western systems that have been hurled to us, and the violence that is in the aftermath is very real, and it is still going on, and it is still like something we experience and bring with them as indigenous people. At one point Zahn and I turned to each other, and I had something like that: ‘It is a scary place to go, but we are the right people to do this. If we do this, it will be you and me. ‘

What about photographing this series?

One of the first decisions I made in the episode was that the day we photograph this scene would be a closed set. We are going to bring in an intimacy coordinator to ensure that Enzo Okuma Linton, who played Will, feels good and that his parents feel good because Enzo is a young native boy in the scene. We also wanted to protect our energies so that we could create the best version of that scene.

One of the most beautiful moments I experienced as a director happened in that scene. We first shot everything with Will and the priest – and that was the choice of Zahn – and then he wanted all his coverage to come to the end of the stage. He must open the truth about what happened to his cousin when he was a child. It is that feeling that you cannot do anything about it because you are a child, and in this case you are a native child, witness something that happens by this priest that has a lot of power in the system with which they are confronted.

We have done different takes, and he was really angry, which is a really understandable expression of witnessing this thing. I went to him and said, “I think you have a little more than just anger to give it, but I don’t want to insist to go somewhere you don’t want to go, and I understand that this is a very complicated thing to respond to.”

So we see this tragic sorrow and the emotion of him, it is anger mixed with shame and sorrow. He gets one rule in it and says, “Erica, I can’t do this alone. You have to come here.”

I cry about it. So I walk to the side of the prison chat, and he is on the other side, and I am an inch out of the shot, and below that his hand keeps my arm through the bars and he gives this astonishing version. It was this moment when you as a director feel familiar and when a native person feels familiar. At that moment both Zahn and I had to let go and trust each other and know that we would be there for each other. We express something that is deeply triggering and is difficult for Indians to talk about and discuss. When we shouted, we knew we had it. Zahn’s version is downright brilliant. If we had not had the privacy of the closed set, Zahn and I would not have had our own experiences in this world that led us to that, if we could not trust that we could open ourselves and be vulnerable, we could not have come there.

As two indigenous people who try to say something very honest and where. It is a TV program and entertainment, they are all these things, but at the end of the day what we do feels in -depth because we have never received this stage to be able to say these things in our own voice, in our way, with our artistic license.

This episode is about monsters that we have in both the literal and metaphorical sense, but also about what we learn from that trauma. You said that you have received your artistic license to tell this story, what does it mean to have it there?

. Many of the lessons are there. When Joe talks with his father on the stump and says his father, “I did the same,” he must go into this memory that he had been captured because it was too painful to remember. He had to go in there and open trauma to forgive himself because of his involvement in the death of BJ. We flash back between the Monster Slayer and the Hero Twins, who conquer the monster. When he sees the bloody handprint, it’s not a sample, it’s a man. That is the lesson of the episode for me, that the things that happened with Indians and historically the things we have tackled were the monsters genocide, the monsters are lack of justice, the monsters are individuals, people who demand this thing to other people. I think that hopefully a lesson that non-native people can remove this episode.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.