The Tylenol Murders’ investigates it responsible

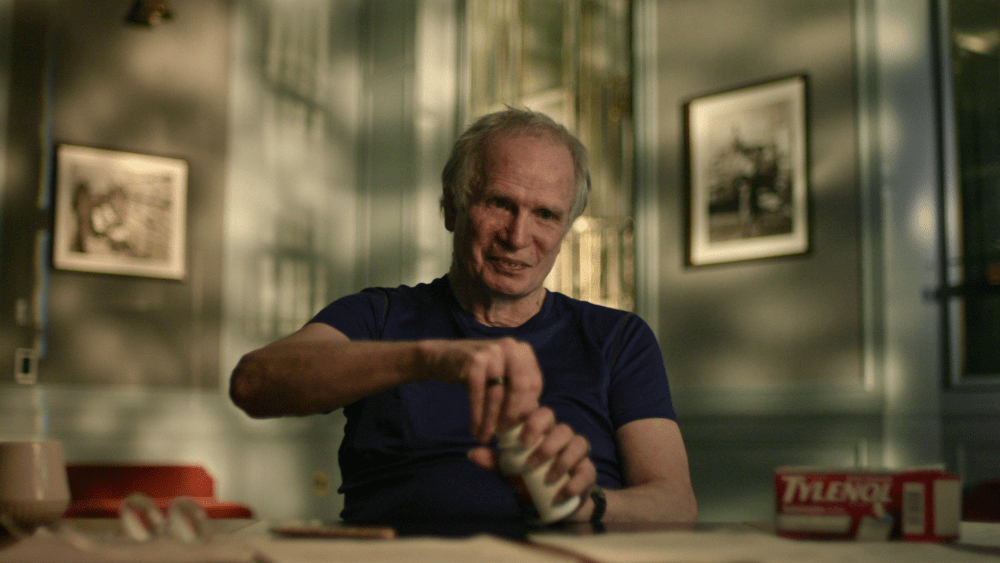

In the morning of September 28, 1982, Mary Kellerman, a 12-year-old resident of Chicago, received a Tylenol tablet by her parents in response to complaints from a sore throat. A few hours later she was dead. Kellerman was the first of at least seven people who would die shortly in succession in the metropolitan area in Chicago after taking Tylenol capsules with cyanide. Those dead and how they happened are the subject of the “cold case of Netflix: the Tylenol murders.”

In the three -part series, directors Yotam Guilderman and Ari Pines visit the frightening dead who have fueled rural panic, who changed a crisis for public health and led to Johnson & Johnson, the makers of Tylenol, to take action quickly and to create sabotitive seals. Before the Tylenol poisoning box, medicines and food products were often filled on stage with only a screw cap and no seal. The series, executive produced by Joe Berlinger, also investigates the case – one of the largest American criminal investigations that have never been resolved.

Through interviews with important players, including FBI agents and the police involved in the case, Guilderman and Pines investigate how the poisoned Tylenol bottles came in the store shelves: Were they deliberately polluted with cyanide? Or were the capsules accidentally polluted in a factory in Johnson & Johnson?

In addition to speaking with important players in the study, Guilderman and Pines (“Shadow of Truth”) also interviewed victim family members, journalists who reported on the murders, as well as the most important suspect of James Lewis. Lewis was sentenced to 10 years in prison for writing a extortion letter about the poisoning, but his DNA was never linked to the suspicious bottles.

“For 40 years, the research was focused in one direction, what the aspect of Jim Lewis is,” says Pines. “What we tried to do in the series is widening the scope. There are more theories there are, and they have a lot of merit in them.”

“The Tylenol Murders” is the second edition of Netflix’s cold case franchise. The inaugural series, “cold case: Who Killed Jonbenét Ramsey”, began to stream in 2024 and was directed by Berlinger.

Variety Speaked with Guilderman and Pines prior to the Netflix launch of the series.

The DOC investigates how Johnson & Johnson has played a role in the Tylenol murders. Do you hope that the series will reopen the case and the investigation into Johnson and Johnson?

Pines: Johnson & Johnson is one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Tylenol is one of their most popular medicines to this day. I think in a case like this, when you realize what was at stake and what is still at stake, it is very important to thoroughly investigate every possible perspective.

The series contains no interviews with a representative of Johnson & Johnson. Have you contacted and requested an interview?

Guilderman: We did that, but they didn’t want to comment. Sometimes that is connected to the fact that large pharmaceutical companies have been under fire for many years now because of the opioid crisis and then the baby powder crisis.

The Tylenol murders have forever changed how we view the products in our medicine cabinets. Do you think people, as a result of this series, will again be afraid of taking Tylenol?

Guilderman: I think safety seals generally work. If the crime happened after the factory, of course. If it was in the factory, we are sewn. But I hope that people will not get afraid, even if it is scary.

Pines: This is a very different kind of real crime doc. In most documentaries we see about murder cases, there is a murderer who actually killed someone physically with a knife or a gun or a kind of weapon. It is usually very graphic. In this case, the murderer was not related to the victims. Not a motive, but there is something very scary in this creepy idea that something like that can suddenly turn into a weapon of mass murder every day as a painkiller.

How did you detect James Lewis and convinced him to do an interview?

Guilderman: Our producer, Molly Forster, was the one who had actually contacted him and led him to speak. She spoke with him and visited him, I think, probably a year before he actually agreed to sit in front of the camera. It was something we knew we had to do for the show, because he is the most interesting character in the show.

The series makes it clear that testing on cyanide after someone dies is not typical. Do you think more than seven people died after taking Tylonel in 1982?

Pines: There are probably more cases. Cyanide is not traceable so quickly. Even law enforcement thinks to this day that there are probably more victims than just seven, probably much more.

Guilderman: I just wanted to add that the fact that all these seven victims were so young, I think the eldest was like 30, there were probably other victims who were older who were probably treated as if they had a heart attack or a kind of natural death.